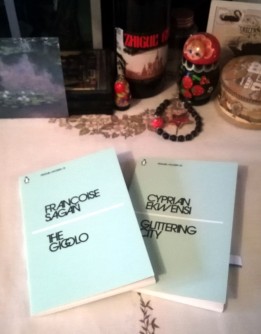

Having got back into my stride with the reading of the Penguin Moderns books, I think I will try to at least read one pair every month – if I can stick to that, I will eventually get to the end! 😀 The most recent duo of bookettes comes from two very different authors: one new to me and one I’ve read before, and both turned out to be most enjoyable.

Penguin Modern 31 – the Gigolo by Francois Sagan

Sagan is the author I’ve read before, and I confess to having had mixed experiences with her writing. I loved getting lost in the atmosphere of “Bonjour Tristesse“; I enjoyed “A Certain Smile” though perhaps warmed to it less; and I found “The Heart-Keeper” very odd indeed… However, the short stories collected here were excellent reading and I have had my faith in Sagan restored!

The four stories are the title one, “The Unknown Visitor“, “The Lake of Loneliness” and “In Extremis“. All, in one way or another, deal with matters of the heart; whether looking at the complexities of the relationship between an older woman and a much younger man, or the discovery that your husband is not what you thought he was, or when dealing with feelings of suicide or incipient death. The title story was particularly powerful, with echoes of Colette’s older protagonists creeping in. And “The Unknown Visitor” was very, very clever at showing how a whole life can be built on a lie which is only revealed in a pivotal moment when the scales fall from someone’s eyes.

Sagan’s writing is excellent and atmospheric, and she captures much in the compressed form of the short story. It’s not a form I was aware she wrote in, and on the strength of these examples I reckon I could be searching out more! 😀

Penguin Modern 32 – Glittering City by Cyprian Ekwensi

The second Modern is an author and a setting (1960s Lagos) new to me, and I was very keen to explore both! Ekwensi was a Nigerian author and as far as I can see, he wrote in English. The author of novels, short stories and children’s books, he had a long and distinguished career; and this Penguin Modern contains just one story; at 51 pages of small type, it’s actually nudging close to novella territory.

“Glittering City” tells the story of Fussy Joe, a musician and wide boy of the highest order. A womaniser, a con man and a completely untrustworthy charmer, he blags his way through life with a deal here, a trick there and women to take care of him in several boltholes. As the story opens, he’s hitting on Essi, a young woman just arrived in the big city; she’ll bookend his tale, appearing at the end of the adventure when we find out what happens to Joe. And plenty does, much of which he deserves…

It’s a fascinating story, if problematic at times for me. Joe is not a character you can like – at least, I didn’t from the very start. He exploits and takes from the women in his life with no regard for their feelings; he’s completely amoral; and to be frank it’s hard to find a single redeeming factor, so that there were many times during the story I was wanting some kind of retribution to catch up with him. And the author presents his story as is, so I didn’t get a sense of whether Joe was someone we were meant to be admiring or despising – I guess I know which side of the line I come down on!

Despite this, the book is an interesting and atmospheric read, and once I got into the second, more action-filled half, I did really enjoy reading it. Ekwensi captured his time and place beautifully, and the story built nicely to an exciting ending. So a satisfying read, and one I most likely wouldn’t have come across if it wasn’t for the Penguin Moderns!

*****

PMs 31 and 32 really were very disparate – almost opposing, in some ways, with women preying on men in one and the reverse in the other! But both made fascinating reading, and I’m definitely inspired to keep going with the Penguin Moderns – after all, I’m nearly two thirds of the way through!! ;D