When Philip at the “A Plunge Into Calvino” podcast announced that the August read for the Italo Calvino bookclub would be “If on a winter’s night a traveller” I was in two minds about whether I wanted to read this again. I’ve always reckoned it to be my favourite Calvino book, and I have a long history with it, back to the time I first read it and it completely changed the way I thought about books and reading. However, it felt as if I’d re-read it fairly recently (certainly within the time of this blog) and so I wasn’t sure if I was in the right headspace to revisit a book which meant so much to me. However with a little encouragement from Philip I decided that I would, and to make the reread even more special I indulged myself by sending off for a lovely Everyman hardback edition (translated by William Weaver) which I thought might make the reread even better. Well, whatever edition I chose to read the revisit was something else, as I’ll try to convey in this post!

Very pretty Everyman hardback…

“Traveller…” was first published in 1979, and when it was recommended to me by a colleague of Mr. K’s, it was in terms of “If she likes books about books, she’ll love this” (they were not wrong…) In simple terms, the book tells the story of a Reader who is trying to read “If on a winter’s night a traveller”, the new book by Italo Calvino. He negotiates the snares of the bookshop to buy a copy, settles down to begin the book and is captivated by the first chapter. However, here his problems start… The book is faulty, with the same section bound into the volume over and over again. He returns to the bookstore to try and get a replacement copy, but is told that mistakes at the printers mean that this is not the Calvino and so he is provided with what is supposed to be the correct book. He and a fellow Other Reader (who receives a name, Ludmilla) try to carry on with their reading…

Alas, this is the first of a chain of faults or issues which results in the Reader never being able to read more than a chapter of a book before being interrupted; and the adventures of the Reader, the Other Reader and several other characters in pursuit of the finished book, or indeed any finished book, become wilder and wilder. Alternating numbered chapters and titled stories take the external reader on a labyrinthine journey through countries, times, political situations and all manner of dramas – will the Readers ever catch up with the book(s) and how on earth is Calvino going to finish the story!?

That’s perhaps a slightly surface level look at what this book is about, because frankly it would probably take me a week’s worth of long post to get anywhere near discussing the many levels of what is a quite dazzling and multifaceted book, and as far as I’m concerned a work of genius. It was my first experience of any kind of metafiction, and the first page still leaves me breathless – the opening sentences sets the tone:

You are about to begin reading Italo Calvino’s new novel, If on a winter’s night a traveler. Relax. Concentrate. Dispel every other thought. Let the world around you fade. Best to close the door; the TV is always on in the next room. Tell the others right away, “No, I don’t want to watch TV!” Raise your voice—they won’t hear you otherwise—“I’m reading! I don’t want to be disturbed!” Maybe they haven’t heard you, with all that racket; speak louder, yell: “I’m beginning to read Italo Calvino’s new novel!” Or if you prefer, don’t say anything; just hope they’ll leave you alone.

This chapter goes on to relate how you (is this you, the external reader, or the Reader who will become the protagonist of the story??) have made your way through the stacks of books in the bookstore fighting for your attention, triumphantly bringing home the Calvino; and it’s a chapter which will resonate with any book obsessive! And the opening lines of the first of the sub-stories, ‘If on a winter’s night a traveller’ does the same thing:

The novel begins in a railway station, a locomotive huffs, steam from a piston covers the opening of the chapter, a cloud of smoke hides part of the first paragraph. In the odor of the station there is a passing whiff of station café odor. There is someone looking through the befogged glass, he opens the glass door of the bar, everything is misty, inside, too, as if seen by nearsighted eyes, or eyes irritated by coal dust. The pages of the book are clouded like the windows of an old train, the cloud of smoke rests on the sentences. It is a rainy evening; the man enters the bar; he unbuttons his damp overcoat; a cloud of steam enfolds him; a whistle dies away along tracks that are glistening with rain, as far as the eye can see.

Again, the novel is talking about itself, and this was a revelation to me. But it needs to be recognised that first and foremost, “Traveller” is a book about reading, the importance of books and reading, and how each reader is an individual with an individual response. The framing device employed here allows Calvino to explore a rich selection of different stories and indeed different types of storytelling (I keep coming back to what a remarkable storyteller he was, don’t I?) Each novel ‘beginning’ is stylistically different; for example, the narrator of “Leaning”, an invalid by the sea, is very precise, trying to control what he sees as chaos around him; and “Around” struck me as somewhat Borgesian; whereas the opening title story is more of a spy story. Calvino’s playfulness comes to the fore here, and I couldn’t help thinking he was having great fun with all these different styles of storytelling.

…you seem to be lost in the book with white pages, unable to get out of it.

You might ask whether it’s a little annoying just having fragments to read but I don’t find this so. Each story breaks off at a pivotal point leading the Reader (and this reader!) very much wanting to know what happens next. Yet somehow the fragments manage to be complete within themselves. As I’ve mentioned, the range of stories is really varied: from spy style narratives through tales of country feuds, a love triangle in revolutionary times, a murder mystery, a tale of a man being pursued by ringing telephones, a Japanese setting to a surreal tale of non-existence, the fertility of Calvino’s brain is stunning. Interestingly, one strand of the book explores the idea that all stories come from one source, with a Father of Stories being sought – I rather think Calvino could qualify for that role!

These individual tales are counterpointed with the chapters about the Reader; as the book progresses, his search for a complete book become as wild and fantastic as some of the stories themselves – which could be (fictional) life imitating art and who knew that reading could be so dangerous! It’s worth noting that this multifaceted narrative involves Calvino the actual author (or does it?), his representative in the book, the Reader, the female Other Reader, the selection of characters in each sub-story and of course the External Reader – yourself! Despite the potential for an overcomplex book, Calvino as always handles his material with a brilliantly light touch.

Another fascinating aspect which is much to the fore in “Traveller” is that of the concept of authenticity, with sub-plots concerning conspiracies, political shenanigans, censorship and whether it matters who actually wrote the book. A translator called Ermes Marana appears at junctures, and seems to be responsible for all manner of falsifications, so much so that certain regimes are hunting him though he’s remarkably elusive. If I’m correct, Calvino’s personal belief was that the author should be fairly invisible, a preference echoed by the Other Reader, Ludmilla, and maybe in our modern world of unlimited visibility we need to remind ourselves that it’s the text that matters. There’s a eerily prescient element recurring in the narratives too, where Calvino introduces bookish technologies which can imitate the style of authors so that computers can write books – another version of the Death of the Author, maybe, and rather pre-empting modern AI!! Calvino also tackles the issue of the sheer amount of books being published, something also very relevant nowadays with our modern publishing methods and plethora of texts appearing left, right and centre…

…the author of every book is a fictitious character whom the existent author invents to make him the author of his fictions.

One of the most interesting chapters for me was the one which was narrated as if from the diary of the author Silas Flannery, one of the writers who recurs throughout the book. This particular chapter really allowed Calvino to explore so many elements of writing and reading and books, and with his need for seclusion and a certain anonymity, I couldn’t help reading this as a sly self-portrait of Calvino himself. Certainly, one of the paragraphs from Flannery’s journal seems to relate to what we might be reading at the moment…

The romantic fascination produced in the pure state by the first sentences of the first chapter of many novels is soon lost in the continuation of the story: it is the promise of a time of reading that extends before us and can comprise all possible developments. I would like to be able to write a book that is only an incipit, that maintains for its whole duration the potentiality of the beginning, the expectation still not focused on an object. But how could such a book be constructed? Would it break off after the first paragraph? Would the preliminaries be prolonged indefinitely? Would it set the beginning of one tale inside another, as in the Arabian Nights?

As I revisited “Traveller” I had to keep stopping and taking a breath to let myself properly digest what I’d just read and make sure I didn’t gobble it down. Although I’ve read this book several times, my last visit was actually in the very early days of this blog, about 11 years ago, and I am certainly reading Calvino with much more attention nowadays. Each re-read of this book brings out more depth and layers, and I was consistently struck by how clever it is – even as you are drawn into and involved with each tale, Calvino constantly reminds you that this is a construct, distancing you from the narrative you’re enjoying but never making it any less compelling. Yet I found I had forgotten the specifics of some of the books the Reader was trying to read and at times felt as if I was encountering the book for the first time, which was quite marvellous. The ending knocked me out completely; I was wondering how Calvino could end such a book, which had become wilder and wilder, but he did it brilliantly and I was left wanting to go back to the start and begin reading all over again!!

In reading, something happens over which I have no power.

Mr K’s colleague was right about this being a book about books, as at the heart of “Traveller” is, I think, the importance of storytelling in our life. Calvino’s audacious explorations of reading and writing and why we do both are thought-provoking and unforgettable. The continuing sequence of issues getting in the way of the reading shows how dependent we are nowadays on many other entities to hear those stories – publishers, printers, bookshops, translators, censors… The element of translation was particularly interesting, with one of the stories depending entirely on the ability of a professor of a dead language to translate a book accurately, and this did remind me of how much I rely on translators (thank you, William Weaver, for all the work you did for Calvino’s books.)

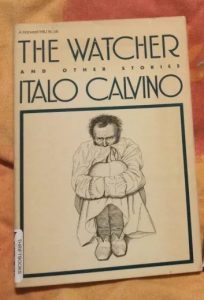

Minerva, original Picador, Vintage editions

I’ll stop here before this post gets any longer, though I am so knocked out by my re-read that I could go on forever (and my book hangover is going to take ages to go away). “If on a winter’s night a traveller” is absolutely dazzling in its conception and execution; an unbelievably clever and complex yet completely readable book, a real masterwork. I have nothing but sheer admiration not only for the fertility of Calvino’s mind, thinking up each of these potential stories, but also his skill in constructing such a narrative. Since I first encountered this book, I’ve read all manner of OuLiPo works using constraints, meta techniques and the like, and I suspect that’s led me to revisit “Traveller” with greater experience and understanding. I probably responded more to it on an emotional level back in my twenties; now I’m looking at it with both emotions and intellect; certainly, I made dozens of pages of notes/quotes while I was reading it, and I could have stuffed this post with quotations. “If on a winter’s night a traveller” is definitely one of the most important books in my life, to which I hope I’ve done justice here, and my re-read has made me appreciate it even more. Perhaps I should spend the rest of the year reading nothing but Calvino….

*****

I wrote this review ‘blind’, you might say, straight after finishing the book, without reading my previous post on it, nor the introduction to the Everyman edition. So what you have above is my unfiltered response! On the subject of the Everyman, it made very easy and pleasant reading – their hardbacks are comfortable to hold, pages flop open nicely, and I was relieved not to have to risk my fragile and a bit crumbly original Picador which is old but precious!

However, I did notice a slight difference between some of my editions. In both the Picador (from 1982) and the Everyman, the contents page and the book itself has the ‘ordinary’ chapters given as Chapter one, Chapter two etc. However, the Minerva and Vintage editions simply have 1, 2, 3 etc. A minor point, maybe, but I wonder why?