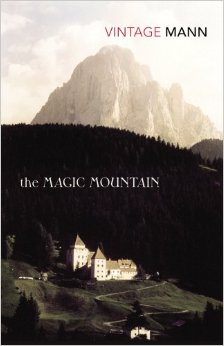

The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann

“The Magic Mountain” was one of the books I considered reading for The 1924 Club but didn’t for a couple of reasons: firstly, I didn’t own a copy, and secondly, it’s over 700 pages long… However both those issues were resolved – I was lucky enough to win a copy of “The Magic Mountain” from lovely Lizzy’s Giveaway, and I decided to embark upon it not for The 1924 Club but for German Literature Month, starting during half-term when I would have more time to read. And a confession: I did own an old Penguin copy once and tried to start it but stalled, so I was hoping I would do better this time.

Mann, is of course, one of the German greats; as Wikipedia tells us, he was “a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novellas are noted for their insight into the psychology of the artist and the intellectual. His analysis and critique of the European and German soul used modernized German and Biblical stories, as well as the ideas of Goethe, Nietzsche and Schopenhauer. Mann was a member of the Hanseatic Mann family and portrayed his family and class in his first novel, Buddenbrooks. His older brother was the radical writer Heinrich Mann and three of his six children, Erika Mann, Klaus Mann and Golo Mann, also became important German writers. When Hitler came to power in 1933, Mann fled to Switzerland. When World War II broke out in 1939, he moved to the United States, returning to Switzerland in 1952. Thomas Mann is one of the best-known exponents of the so-called Exilliteratur, literature written in German by those who opposed or fled the Hitler regime.” That’s quite a bio…

“The Magic Mountain” tells the story of Hans Castorp, a young German orphan, living pre-WW1. Brought up in the main by his grandfather, who is now also dead, he has a network of rather formal relations and as a trained engineer, has his life and career planned out. Before starting work in shipbuilding, he journeys up the mountains to the Berghof sanitorium in Davos, a Swiss Alpine location; here he is to spend three weeks visiting his cousin Joachim, who is being treated for consumption. As the introduction reminds is, tuberculosis was a killer in these pre-antibiotic days, and the rarefied atmosphere of the mountains was thought to be beneficial (I was reminded of Katherine Mansfield’s constant searches for health). Joachim is a rigid young man, desperate to be cured so he can go off and join the army. The cousins are attached but reserved, addressing each other formally and maintaining the social structure of the world down below.

Initially, Hans is amused by the routines of the Berghof and the cures the inmates take; however, he’s having trouble becoming acclimatised, at one point having a dramatic nosebleed; and when he appears to catch cold he asks the doctors to check him over. It transpires that he has a “moist spot” himself and it’s suggested that he stays up at the sanitorium for a few months to be cured himself. However, what starts as three weeks, then a few months, finally ends up being a seven-year stay and during that time Hans goes through many changes. Because of the cosmopolitan collection of inmates, his views are subject to much change; his moral standards relax; he falls in love; and through meeting some powerfully opinionated thinkers, he receives an intellectual education he would never have had down in the ‘flat-land’.

TMM is a massive book and to go into any more specific plot description would be pointless. It’s a novel of ideas; of cultures clashing and changing; and also one of enchantment. The seven-year period which Hans spends away from normal life is almost like a fairy-tale, in which the characters make their own reality, and the reader does wonder if they’ve all been bewitched. Hans ascends the mountain as if entering another realm; which in a sense he is, as the difference between the land of the living down below and the land of the dying up high is pronounced. There is a real ambiguity about the illness of the patients, and particularly with Hans we are never quite sure if he is really ill, or if it’s just the effects of the altitude. There’s a slight hint that the doctor, Hofrat, is a bit of a charlatan, and the treatments do seem to go on and on. This has a particularly striking effect on Joachim who, in his desperation to join up with the army, defies the doctors and flees from the enchanted region, with disastrous results.

Indeed, the Berghof seems to almost have a hypnotic effect on visitors which is demonstrated when Hans first arrives and becomes rather insidiously assimilated into the place’s way of life, and also when his Uncle James visits. In fact, it’s not until we see Hans encounter his uncle from the ‘flat-land’ down below, come up on a recce to find out exactly why his nephew is lingering in the mountains, that we really appreciate how much the former has changed. From a stiff, slightly upright bourgeois, with a career all mapped out for him, he’s grown into a pseudo philosopher, ready to explore ideas and grab what life can offer him away from the constraints of normal society. At several points, Mann describes what Hans has found in the higher regions as freedom, and it certainly seems to be a liberation of sorts, with the falling away of the rigid norms of the pre-WW1 society – but to be replaced with what? The inmates dabble in all sort of crazes, from playing patience through stamp collecting and even to holding rather disturbing seances.

There’s also a wonderful satirical element in the writing, as Mann wryly observes the various residents of the sanitorium; from the ‘bad Russian’ table; through Frau Stohr who always manages to say the wrong thing, or something totally inappropriate; Frau Chauchat, the beautiful Russian woman with whom Hans falls in love; the complex doctor Hofrat who’s also an amateur painter; Settembrini, an Italian patient, and Naphta, who lives in the nearby village. The book is full of wonderful, memorable characters, all of whom have some effect on Hans. In fact, Hans Castorp goes up the mountain as no more than a boy; rigid, naive and tradition bound. He comes down it a man, with a wealth of experience; because up in the heights, in that rarefied air, he’s experienced all that life has to offer.

Interestingly, I’ve heard TMM referred to as one of a number of “novel-essays” and it could certainly be argued that the book has a didactic purpose; the long sections of intellectual discussion are a way for the author to sneak plenty of high ideals into the tale. The clash of ideas, nationalities and cultures is central to the book, and there are many ideas discussed here (some of which, I have to confess, lost me a little…). Intellectual reasoning and debate is represented by the Freemason, Settembrini and the Jesuit, Naphta, both of whom are involved in Hans’ emotional and spiritual development. Settembrini’s pontificating, and his constant mental battles with Naphta, dominate whole chapters of the book. It’s as if they represent the two polar opposites of belief in the society of the time and, as Hans remarks, are battling for his soul.

They forced everything to an issue, these two – as perhaps one must when one differed – and wrangled bitterly over extremes, whereas it seemed to him, Hans Castorp, as though somewhere between two intolerable positions, between bombastic humanism and analphabetic barbarism, must lie something which one might personally call the human. He did not express his thought, for fear of irritating one or the other of them; but, wrapped in his reserve, listened to one goading the other one…

However, there are so many strands running through the story: illness and death is naturally prominent; the passing of time and the perception of time, which is very different away from the flat-land; magic and enchantment, of course; and the importance of music. The sanitorium in the mountains is a rarefied atmosphere in more ways than one; not only is the altitude relevant to the consumption cure, but in the isolated world of the patients, where they almost regard themselves as superior to the rest of the world, any kind of behaviour is sanctioned. There is a sense that by being physically removed from, and high above, the flat-land, they have a better overall view and are in a better position to judge.

As the story builds to a climax, with hints from the outside world that all is not well (hints that Hans tries to ignore) there is a growing sense that something will break. The characters begin to behave in more eccentric and dramatic ways, and the rivalry between Settembrini and Naphta becomes much more extreme. When that climax is reached, modernity and reality come crashing into the book and the shock to Hans’ world (and also to the reader) is palpable. The enchanted hero on the magic mountain is only released from the spell by the thunder crash of war, and the contrast is devastating.

As Mann explains in a fascinating afterword to the novel, the story grew out of a stay he had in a real-life sanitorium which he then used to build his book of ideas onto. He recommends that you read TMM twice, and it’s a view with which I would probably concur. It’s impossible to do more than scratch the surface of this vast, involving and complex novel in a review of this length; it raises so many thoughts, theories and questions that you could probably spend a good few years studying it. As it was, I came out TMM with a sense of having lived on the mountain with Hans, joined him in his triumphs and tragedies, and experienced a world in translation. I can see why Mann is regarded as one of the greats, and I’m sure this isn’t going to be the last of his novels I read.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 08:25:36

I’ve not read this, always looked a bit daunting. I can recommend Buddenbrooks though, a sort of Hanseatic Forsythe saga.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 09:11:44

I reckon if you can manage a huge family saga, you can read this! I *have* heard good things about Buddenbrooks – it’s on my radar!

Nov 21, 2015 @ 08:37:07

Excellent review, Karen – really terrific stuff. I had no idea that Mann had drawn on his own life experience as inspiration for this novel.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 09:07:52

Thanks Jacqui! I didn’t either, until I read the afterword. It’s an excellent and thought-provoking read, and I *do* want to read more Mann now!

Nov 21, 2015 @ 08:45:04

Brilliant review. The Magic Mountain sounds fascinating and rather daunting in equal measure.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 08:48:39

Oh, definitely both – my ascent of the mountain (chronicled in a diary review) was certainly an exhilarating but arduous one 😉

Nov 21, 2015 @ 09:06:45

Agreed – there were times when I struggled but I’m glad I did!

Nov 21, 2015 @ 09:07:08

That’s a good way of putting it – it certainly was a wonderful read, if a little difficult at times.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 08:55:35

What a wonderful review! Like many people I too have a copy of this book awaiting, in my case a handsome modern library edition. I love the cover of yours, I don’t think we get those Vintage editions here. But, of course looks means nothing if the book stays on your shelf. I shall bookmark your review as inspiration and a guide when I finally climb that mountain myself!

Nov 21, 2015 @ 09:06:26

Thank you! It wasn’t always an easy read, but it was fascinating and absorbing and most definitely worth reading.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 09:53:05

Wonderful review 🙂 I have a copy and its one that I need to read for my Le Monde reading challenge, but the thought of it is overwhelming & I keep running away! You’ve made it seem much more approachable now.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 15:10:06

Thank you! It *does* need commitment, but it’s worth it – I felt the rewards outweighed the occasional complexities of ideals and ideas!

Nov 21, 2015 @ 11:13:18

Like many peoole here, I alsi have a copy – an old Penguin copy. Was your versuin a new translation?

The book is so appealing and yet I never get round to reading it. The characters almost sound as if they’re like Greek gods, up in the heavens, discussing abstract idaes and commenting on the mortals’ behaviour down below.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 15:09:09

Oh, how remiss of me – I normally credit the translators because without them my reading experiences would be so much the poorer! This version is by H.T. Lowe-Porter, from 1927 according to Wikipedia, so your Penguin may be the same. There is a more modern Everyman one, which I had a quick look at, but I personally preferred the language of this one, especially as it’s contemporary with Mann. Yes, that’s a good analogy – there certainly is a sense of the residents being aloof and detached from the everyday world which is probably why they’re able to get into such deep debate without the everyday distractions.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 11:18:37

Marvelous invitation to this towering classic. You make it sound really a must read for me. Thank you.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 15:04:44

Thank you, and you’re welcome. I can certainly see why it has classic status and it *does* deserve it.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 12:18:46

Gosh Kaggsy, you have made Mann, whom I seem to have somehow omitted, during the time in my life when I was submerging myself in challenging European Classics, demand to be noticed. Whether he gets into line in my sequential reading the twentieth, or whether he demands to be read earlier, off challenge, A Mann will certainly happen. Perhaps Madame Bibi and I will embark together on our separate challenges, with this!

Nov 21, 2015 @ 15:04:13

I’m kind of amazed I never read him before myself – even if it was only Death In Venice or a shorter work! But he most definitely should be read by anyone with more than a passing interest in European lit. I’ll follow your challenges with interest…. 🙂

Nov 21, 2015 @ 12:30:33

Grear review! It sounds like an epic read!

Nov 21, 2015 @ 15:02:55

Thanks! Yes, epic is the word – fortunately I was in the mood for a big book!

Nov 21, 2015 @ 14:14:13

Fantastic review! For the first time I feel properly inspired to read this! And I’d second Buddenbrooks if you are interested in more of Mann, and Susan Sontag’s Illness and its Metaphors if you’re curious to learn more about the way tuberculosis was understood and used in literature. But I really am so impressed that you made it up and down the mountain, and got so much out of the journey.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 15:02:34

Thank you!It wasn’t always an easy journey, and I’d be fibbing if I said there were no difficult bits – but it was a worthwhile one and I’ll obviously have to look out for Buddenbrooks!

Nov 21, 2015 @ 17:33:59

I recommend Dr Faustus.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 21:34:47

Thank you – I’ll keep an eye out!

Nov 21, 2015 @ 14:45:23

Fascinating! The perfect plot — and location — for a Wes Anderson film.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 15:01:19

Hah! I’ve only ever watched The Grand Budapest Hotel (which I loved) but I get what you mean! 🙂

Nov 21, 2015 @ 15:35:20

You remind me of how a girl I knew in college gave me this book to read. We were co-workers at the college book store at the time, and would talk about books whenever we could. I think I was just too busy with other official college related reading to read it so I never did. I gave it back to her unread. She never spoke to me again.

“That’s all for the best” says my wife.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 15:37:09

I think your wife is right…. 🙂

Nov 21, 2015 @ 15:44:19

Yes, she is!

I think you wrote in a previous post how it is one of those books that was popular among college students. It seems to have held up better than a lot of other books like that.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 16:03:26

Yeah, I think personally that some books do survive later re-readings better than others. I would struggle to go back to “The Catcher in the Rye” I think, but Hesse certainly and most of the French authors I love I still find great.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 17:31:54

It is indeed superb and you have written an excellent review. My much shorter one is here: http://morganas-cat.tumblr.com/post/18600147530/the-summit-attained and in that post I refer (backwards in time again) to what finally spurred me to read it – you might be surprised!

Nov 21, 2015 @ 21:36:58

Thank you, and I *was* surprised – I’d never heard of the TinTin novel! But I agree with you about TMM being about time – I found some of his thoughts about our perceptions of its passing at differing rates very enlightening.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 17:43:24

I really enjoyed reading your review. I was one of those college students who read TMM and now i feel i want to try it a second time. I consider TM to be a kindred soul, though i must admit, i was completely overwhelmed by the abundance of topics in TMM, and maybe this is just something TM intended, like Wagner did with his music, the dionysian principle at work, so to say.

Nov 21, 2015 @ 21:34:32

Thank you! There certainly is a lot to consider in TMM – it’s just stuffed full of ideas and I imagine would stand several re-readings (if I had the time).

Nov 21, 2015 @ 21:42:14

I’ve just finished reading Death in Venice and Other Stories for German Literature Month. It’s the first time I’ve read Thomas Mann and I enjoyed the title novella but found the rest of the book quite uneven. I’m not really a fan of the short story format, though, so I’m looking forward to trying one of his longer novels. Maybe I’ll tackle this one soon!

Nov 21, 2015 @ 21:48:34

I like short stories but I’ve never read DiV though I really should. This is definitely worth reading, though you do need to invest a bit of time…. 🙂

Nov 22, 2015 @ 10:19:34

Now that’s what I call a thoughtful review that makes those who don’t know this marvelous book want to read it – or in my case to re-read for the fifth or sixth time. It is interesting that I discover every time new details and that my focus shifts every time a bit. You are right, there are many satirical elements – don’t forget Mijnheer Peeperkorn (an easily recognizable portrait of Gerhart Hauptmann, who was reportedly not amused). The chapter about music is for me the central part of the book and the verbal arguments of Settembrini and Naphta (both of them based also on real persons) are another one. The Magic Mountain was written when Thomas Mann had overcome his flirt with nationalism and approached a new phase in his life as an ardent defender of the Weimar Republic, so it was a time of reorientation and it shows in the book.

Nov 22, 2015 @ 11:04:53

Thank you! I can well believe that every re-read reveals more. Peeperkorn was a wonderful character, and the chapter about the music was incredible. Definitely most impressive!

Nov 22, 2015 @ 11:19:06

I read this about four years ago in the same translation. I now have the James Wood translation and hope to read it soon. Your review was brilliant. I read for German Lit Month his Buddenbrooks The Decline of a Family and loved it.

Nov 22, 2015 @ 12:00:18

Thank you! I really will need to read Buddenbrooks – it’s having so many recommendations!

Nov 23, 2015 @ 08:52:24

I have always been a coward about this and its massive heft so don’t even own a copy. Deep down I think i worry I might not be able to concentrate enough (I do most of my reading either on the morning commute on the tube or just before going to sleep) and yet I really want to! Apologies for the sideways glance am my reading peccadillos – really enjoyed the review Karen 🙂

Nov 23, 2015 @ 09:30:57

That’s why I started it when I wasn’t at work – I often read at night and that isn’t necessarily the best time. The difficult bits are the chapters of philosophising, but they *are* worth persevering with!

Nov 27, 2015 @ 10:02:34

You really do the book justice in your review, going into more depth and trying to unravel all the plot elements (well, I say plot loosely). You’ve made me want to reread it. I remember I read it during a summer vacation that I was spending in the mountains and I keep thinking I was ill myself when I read it (but perhaps I was just imagining it, influenced by my reading matter).

Nov 27, 2015 @ 10:35:43

Thank you! I must admit I kept imagining I had all sorts of things wrong with me as I read this, but I comforted myself with the fact that we have antibiotics nowadays…. 🙂

Dec 07, 2015 @ 11:21:22

I’ll echo others by saying great review Kaggsy. I’ve read a couple of Mann’s, but not this one (because as you say it’s 700 pages long). I do hope to, and you make it sound worth the effort which frankly with that many pages is good to know in advance. If one is going to scale the mountain, it’s nice to know the view from the top is worth it…

Dec 07, 2015 @ 11:28:42

Thanks Max! Yes, it *is* a commitment but I think it’s worth it. The view is impressive and enlightening…!

Dec 10, 2015 @ 05:03:32

Dec 31, 2015 @ 07:25:26