As has become a tradition, Mr. Kaggsy has offered up a review for the #1937Club and this time he takes on a book and author who have been much loved – though I wonder how much they’re read nowadays? The title is “The Citadel” by A.J. Cronin, and I think Mr K. was a little underwhelmed…

Archibald Joseph Cronin (born 1986, Dunbartonshire, 1896; died 1981, Montreux) was both a doctor and prolific writer. He trained at hospitals in Scotland and Ireland, subsequently entering general practice and later having a practice in Harley Street, London. His most famous novel, “The Citadel” (1937) is hailed as having led to the establishing of the UK National Health Service in 1948, having fictionally exposed inequity, incompetence and misconduct in the medical profession.

As with “The Citadel”, many of Cronin’s books became bestsellers, also being adapted for the cinema and radio – one of the latter being produced in 1940 with Orson Welles – as well as being much translated. The publishing of “The Citadel” resulted in resistance from medical sources, there even being moves to have the novel banned. However, the book has remained in print and the screen life of “The Citadel” included the 1938 US MGM earliest film, starring Robert Donat, plus three television versions in 1960 (twice) and 1983.

In time, another of Cronin’s creations, Doctor Finlay of Tannochbrae, appeared as short stories (1978) and as “Dr Finlay’s Casebook” (2010), also enjoying a long run on British TV as Doctor Finlay (1993-1996) and the earlier Dr Finlay’s Casebook (1962-1971; based on Cronin’s 1935 novella “Country Doctor”).

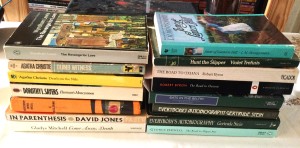

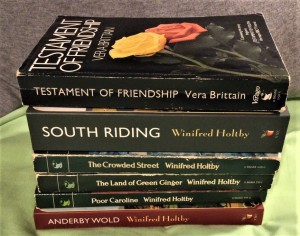

First edition Victor Gollancz 1937 and reprint 1939; Little, Brown 1938. US publishings and Hollywood adaptations led to the author and his family living in America for several years.

And so, on to “The Citadel”, a novel of its time, but with a lifespan stretching into the present century. The 2019 Picador paperback included an introduction by Adam Kay, best-selling author of “This is Going to Hurt: Secret Diaries of a Junior Doctor” (Picador, 2017), which was itself made into a BBC TV series in 2022. “The Citadel” became publishers Victor Gollancz’s highest ever selling book, with Cronin being claimed as the most successful novelist of the 1930s, along with the novel winning the US National Book Award, Favorite Fiction of 1937.

The story opens in 1924, with Andrew Manson starting out as a doctor in South Wales. As he travels by train to his new area he is filled with overwhelming exhilaration springing from the hope and promise of the future. Upon arrival he is told Last assistant went ten days ago. Mostly they don’t stop. At the home of the practice doctor, the newcomer discovers the senior to be seriously ill, meaning Andrew will likely be working more as the replacement than assistant.

Barely recovered from travelling, Andrew is needed for a house visit, answering the call without hesitation. He is nervous of making his first examination, a young woman in bed, the husband looking on. His diagnosis of a ‘chill’, he realises, is deficient, more likely an infection, one which needs medication. As he mixes this back at the surgery, a male assistant to another doctor insolently instructs the entrant. I realise you’re just passing through on your way to Harley Street, but in the meantime there are one or two things about this place you ought to know. You won’t find it conforms to the best traditions of romantic practice. There’s no hospital, no ambulance, no X-rays, no anything. If you want to operate you use the kitchen table. You wash up afterwards at the scullery bosh. The sanitation won’t bear looking at. In a dry summer the kids die like flies with infantile cholera.

After an unsatisfactory night’s sleep, the novice arrives early at the surgery, finding the dispenser, Jenkins, already present. One imparted piece of information is alarming. You don’t have to be so early, doctor. I can do the repeat mixtures and the certificates before you come in. Miss Page had a rubber stamp made with doctor’s signature when he was taken bad. Jenkins has an equally disconcerting instruction ready, as he pours water, ready to be dispensed. We know what good old aqua means, eh, doctor, bach. But the patients don’t. I’d look a proper fool too, wouldn’t I, them standin’ there watchin’ me fillin’ up their bottles out the tap.

Worse is on its way, as Andrew later suspects, from learning of more local cases, that a enteric infection has broken out. Advice given to him is far from comforting. If you should run into anything very nasty ring up Griffiths at Toniglan. That’s fifteen miles down the valley. He’s the district medical officer…But I’m afraid he’s not very helpful. Attempts to contact the advisor are fruitless, the young doctor being told, You’ll never find Doctor Griffiths in Toniglan this hour of day. He do go to the golf at Swansea afternoons mostly…I wouldn’t waste my time on him if I was you. An assistant has the likely answer, It’s the main sewer that’s to blame. It leaks like the devil and seeps into half the low wells at the bottom of the town. I’ve hammered at Griffiths about it till I’m tired. He’s a lazy, evasive, incompetent, pious swine.

Bantam Books 1951 and 1962; New English Library 1972.

At the end of the first month, Andrew’s patients are all doing well, his intervention having contained the outbreak. As the days pass, his encounters with internal politics and work-shyness become the norm. His seeking of a second opinion in one case produces a galling response, Dr Bramwell giving a cursory glance at the patient abed. He shook hands and hurried off, leaving Andrew utterly nonplussed. His entire conduct at the case betrayed his ignorance. He simply did not know.

Andrew reflects on one cynical view which has been expressed to him, … that all over Britain there were thousands of incompetent doctors distinguished for nothing but their sheer stupidity and an acquired capacity for bluffing their patients. Meanwhile, his local input results in an imaginative way to rid the community of the putrid sewer and gain a new one, the process involving some dynamite. Such are the ways of taking charge, in that nobody else is likely to. The doctor now has a grip on the area, the practice personal and the local people.

The story carries on with anecdotes, meetings, cases and social interaction. In due time Andrew is interviewed for a new post, one preferring applicants to be married. The opportunity presents itself for him as doctor and prospective husband to take up the position and enjoy living in the provided house with his, hopefully, soon-to-be wife, Christine. His interview is successful and as he leaves he jubilantly takes in the new surroundings, much improved compared to his present setting, and with a nice little hospital, as he had been told. More joy is to follow, as his marriage proposal is accepted.

Andrew approaches his first day at the West Surgery with exhilaration, although his caseload turns out to be a succession of people needing a sick certificate, with presently forty waiting, no time for proper consultations and a fair proportion of them looking quite able to work. Worse still, one individual has not been examined for seven years.

At a future point the good doctor loses his temper in the practice and is advised to …go slow, go easy, look before you leap! However, poor medical methods continue to inflame him, while he falls fouls of a nurse who eschews his new-fangled ideas of somebody that’s been here no more nor a week. As for the hospital, the doctor finds that it is in the control of his senior and that the junior is only required for processes such as anaesthetics. He unloads his feelings onto his wife, feeling bitter as to how he gets dragged off his case when it goes into hospital… and … loses the case as completely as if he’d lost the patient. It’s part of our damn specialist-G.P. system and it’s wrong, all wrong!

By the end of the year the physician is gaining a social life, he and his wife being wined and dined. With winter’s passing, Andrew has a new impetus, wanting to find better treatments for longstanding conditions and illnesses, linked to local working and living conditions. A prevailing view is that these things are a fact of life, something which the keen doctor can neither accept nor understand.

The first several years pass, during which the story takes in professional, procedural and medical situations, with continuing glimpses of Andrew’s domestic and social life. A disciplinary matter arises, leading to the doctor having to defend his lengthy studies into lung conditions associated with unhealthy working situations. Although a majority decision is in his favour, Andrew feels compelled to give a month’s notice, leaving behind an unsatisfactory post and its, to him, unacceptable practices.

New English Library TV tie-in 1983; Orion Publishing Co 1996; Picador 2019.

A position as medical officer with the Ministry of Works is taken up, in London, although Andrew is frustrated at the more administrative side of his appointment and general inertia of various august bodies. Whereas he has been keen to pursue his respiratory research, he is instead tasked with looking into uniformity of such things as dressings and the like, to standardise equipment in factories and mines. The work was imbecile. It consisted in the inspection of the first-aid materials kept at different collieries throughout the country: splints, bandages, cotton wool, antiseptics, tourniquets and the rest.

Attending the scene of a serious motor versus bicycle accident has Andrew saving a life and realising that he is not furthering his own career. The doctor seeks to fill a vacancy in a London practice, one with a long-established principal, a gentleman who will likely not be dislodged in the short term. To his wife he sounds off, It’s pretty damnable, Chris! The way these old fellows hang on with their back teeth. And you can’t prise them loose unless you’ve got money. Isn’t that an indictment of our system!

After weeks without a solution, an opening arises, …all at once Heaven relented and allowed old Doctor Foy to die, painlessly, in Paddington. Before long, Andrew, now thirty, has his plate on the door. However, the small payments received for medical assistance are not providing much in the way of income, … It’s the system, he thought savagely… There ought to be some better scheme, a chance for everybody— say — oh, say State control! He also hungers for medical friendship. His burning thought is to become attached to one of the London hospitals, thereby effectively being a consultant.

Now, with more substantial cases to handle, there arose another procedural issue, Many of his cases were urgent — surgical emergencies which cried aloud for immediate admission to hospital. And here Andrew encountered his greatest difficulty. It was the hardest thing in the world to secure admission, even for the worst, the most dangerous case. Fortunately, Andrew’s practice improves, with more patients being on his panel. Gradually, a more affluent patronage is secured, with increased remuneration for the doctor. A guinea a visit — it was three times the largest fee he had ever earned! In seeking first-class patients, he needs to buy some smarter clothes, thus gaining more recommendations.

Soon, now owning a car as well, Andrew’s income is rising, one consultation paying five guineas. He enjoyed receiving cheques now, and to his extreme satisfaction more and more of them were coming his way. However, his wife is the conscience of the pair, not relishing seeing her husband’s name in society publications covering lunches which he had attended. At last, an opening comes up at the Victoria Chest Hospital, in Battersea, and Andrew begins occasional duties at the out-patients department, a relic of the eighteenth century. In time he also leases a consulting room for his private practice, where he will be able to hold his better-class consultations; some further networking brings in more private patients. Sadly, the rise in prosperity saddens Christine, herself feeling that she might no longer be the right wife for Andrew.

A tragedy occurs sometime after, as a result of a botched operation which Andrew observes. As more time passes, he questions his present medical life, the increasing money making his work seem unworthy. After some soul-searching there is an epiphanic change of mind and a reconciliation with Christine. ‘Wouldn’t it be wonderful, dear, if we could form a little front-line unit… a kind of pioneer force to try and break down prejudice, knock out the old fetishes, maybe start a complete revolution in our whole medical system.’

The latter part of the novel deals with a tragic loss and, latterly, a taut situation which provides a lead-in to the approaching close of the story. This reviewer found the book well-intentioned, but of its time, a melodrama. The liberal dialogue and domestic scenes at times are a distraction from the thrust of the medical saga. However, that said, the disapproval of then current standards and practices provides a powerful argument to dismantle the old, pre-war customs and put in place a more standardised system, without the financial and controlling interests.

Clearly, the decades of reprinting, translations and screen or radio adaptations testify to the worthiness of the novel, along with Cronin’s other works. However, the treatment of the central character did not seem to make him always to be as crusading as was expected, at times allowing good and bad fortune to pave the way towards the goal sought. Nevertheless, “The Citadel” is an easy, spirited and sincere read.

Well, thanks for your review, Mr. K. It seems that the book may have been pioneering in many ways but perhaps hasn’t necessarily aged well. An interesting slice of social history, though, if nothing else!