Today’s book for the #1937Club is one that’s long overdue some attention, lurking as it has been on Mount TBR since its reissue in 2014 (ten years ago – OMG!!!) It’s a release from indie publisher Michael Walmer, and was the first in his ‘belles-lettres’ series. A chunky and handsome volume, it’s “Letters to a Friend” by the esteemed author Winifred Holtby, and it makes absolutely fabulous reading.

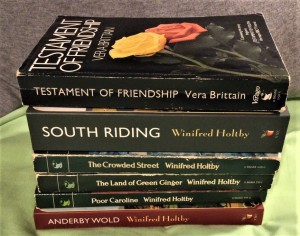

Holtby is probably best remembered now for her novels, in particular “South Riding”, which is something of a classic; and her novels have been published by Virago (many of them also lurking on the TBR…) However, in her time, she was something of an activist, mixing with a fascinating range of people, and the letters reveal much of her life.

Holtby was born in Yorkshire in 1898 to a prosperous farming family; educated at home and then at Queen Margaret’s School in Scarborough, she passed the entrance exam for Somerville College, Oxford in 1917. However, Holtby delayed her entry, instead joining the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), and in 1918 was sent to France. It was here that she met Jean McWilliam who was the commander of her camp; Holtby became her hostel foreman and the two women became firm, lifelong friends. However, post-war, McWilliam moved to South Africa and the book collects the many letters Holtby wrote to her friend until her early death in 1935.

It has to be said up front that Holtby is a marvellous correspondent – anyone would love to receive letters of this calibre! Addressing her friend as Rosalind and signing herself, almost always, as Celia (in reference to the two cousins in “As You Like It”) Holtby relays events from her life, reflections on the changes taking place in the world, impressions of London through the seasons, thoughts about the latest books and plays, and much, much more. The period immediately after the First World War was one of change, with society trying to come to terms with the devastation wrought by that conflict and to build a newer, better world. Holtby was heavily involved in the League of Nations, having pacifist and feminist views, and this led her to giving talks and lectures, attending meetings, and even standing on Hyde Park Corner (or indeed any street!) and simply starting to talk to the public!

As I said above, she’s remembered nowadays for her novels and also for her great friendship with the novelist Vera Brittain, and the latter features all through the book in Holtby’s letters. I’ve read that Brittain could be a difficult woman (which is understandable as she lost close friends, a fiance and a brother in the war); however, apparently the picture she left of Holtby is often an unkind one. McWilliam, I think, would have none of that, and the letters in this collection show Holtby as intelligent, committed to causes and so often displaying a wonderfully positive view of life.

We talked about burlesques and school discipline and Dostoievsky and porridge, and whether bread and cheese and beer are really better than stuffed olives and champagne, and neckties and dons and all the thousand and one silly things that one talks about on a long morning when the air is frosty and the roads are dry.

Holtby’s letters reflect her deep involvement in social causes; she was also a prolific journalist, producing pieces for whoever would take them, and as the years moved on she became more able to publish. The letters also contain her reflections on her novels as she wrote them, and she most definitely lacked confidence in them. By the time of her death, she’d published six novels as well as poetry, short stories and non-fiction. Yet she never seemed satisfied with the books, and she was working on “South Riding” at the time of her death; publication was arrange posthumously by Brittain.

Despite her self-doubt, Holtby was a sparkling, engaging correspondent, not afraid to engage in debate about the issues of the time and always clear about her affection for her friend. The letters do thin out at the end and I wondered if this was because life was busy and getting in the way of writing, or because of the editing process. The collection was put together by McWilliam and Holtby’s mother Alice, and released of course in 1937; it may be that there were personal issues or views that they were uncomfortable including. However, the picture that emerges of Holtby is a compelling one; a committed woman, a loyal and caring friend, and someone who always tried to help those she could, she’s a person I would like to have known.

Holtby always comes across as very human, in that she’s not afraid to change her mind, explore other points of view and indeed questions herself and her attitudes on a regular basis. However, she does hold back from committing completely to something like the socialist cause; I suspect because of her background and upbringing, and even after years of helping the less well off, she can still state: “I agree with Bernard Shaw that poverty is a crime, not a misfortune, and that what’s wrong with the world is not that there are rich capitalists, but that every one is not sensible enough to be a capitalist.” I have to say that we would disagree on this one!!

A few words on this edition; as I mentioned, Michael Walmer re-issued this in 2014 and it’s basically a facsimile of the original edition. Being a book from 1937, there is terminology which would not be acceptable nowadays, despite Holtby’s openness towards other races and creeds. Interestingly, she was aware of the colour issue, particularly as McWilliam was living and working in South Africa; although she doesn’t pontificate particularly deeply on the difficulties there. The Irish problem, too, concerned her greatly. I did find myself brought up short a couple of times by the contradiction of someone who seeks equality for all on one page then saying on the next page “we are going to have a servant”; but of course Britain was still very much a society based on class at that point! Being an older reader (!) I got most of the references in the books to events and institutions (the only notation is minor and provided by McWilliam at the time), but I suspect a younger reader might require Google to clarify some items!

But in the end this is such a fascinating read, and opens your eyes to what life was like in the years when you didn’t go out and buy your clothes off the peg but instead made your own, or had them made for you, and a couple of items had to do for a season! The glimpses of everyday life are one of the most fascinating aspects of Holtby’s letters, and they’re valuable for that alone. They also cover her relationship with Vera, her meetings with Stella Benson, Rose Macaulay and many others, and all in all, these letters make an absorbing collection. Much of her thought on the state of the world and the need for countries to live in harmony is sadly still very relevant, and I do feel that we’re missing intelligent commentators nowadays.

I hadn’t intended to read Holtby’s letters when I first made my list of possible reads for 1937, but in the end I’m really glad I did. She was a wonderful writer; warm, intelligent, humorous and always concerned for her friends and for others. “Letters to a Friend” is a brilliant read, and I really *must* get round to reading some of her fiction!!