As has become a tradition here on the Ramblings, Mr. Kaggsy once more offers up a guest post for our Club reading weeks! Here he explores a book which I’ve previously read and loved and so it will be interesting to see how our views of this particular title differ!!

La invención de Morel by Adolfo Bioy Casares (1940)

Translated as The Invention of Morel, by Suzanne Jill Levine (1964)

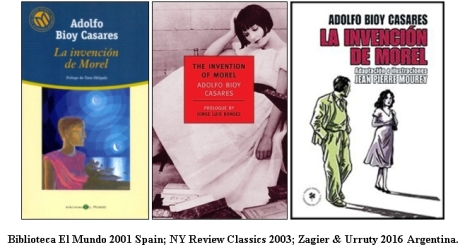

Vast amounts have been written about this book, belying its compressed length. ‘The Invention of Morel’ (TIOM), despite being a novella of around 30,000 words, has given rise to two direct movies – along with other screen creations influenced by it – and an operatic adaptation, as well as garnering generations of reprints, translations and diverse cover designs. Loosely referencing H.G. Wells’s ‘The Island of Doctor Moreau’, hence the name similarity, the author’s work has gained increasing recognition in more modern times; some say its content envisioned future media, and in this respect today’s fantasy video experiences come to mind.

Adolfo Bioy Casares (1914-1999) was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and after publishing several books, also collaborating with fellow author Jorge Luis Borges, his seventh book TOIM gained him First Municipal Prize for Literature in his home city, launching his reputation as a major Latin-American writer. Borges provided the prologue to the book, extolling the ‘odyssey of marvels’ being unfolded within the covers, ending with, ‘To classify it as perfect is neither an imprecision nor a hyperbole.’

Bioy, as he was usually called, put the reader between fantasy and reality, with allusions to immorality and a spiritual world beyond death. The journey and encounters of the unnamed principal character become both cosmic and metaphysical, laced with his fear, thus presenting an ominous adventure. The tale’s opening has the lone man reaching an unknown shore, ‘Now I am in the lowlands at the southern part of the island, where the aquatic plants grow, where mosquitoes torment me, where I find myself waist-deep in dirty streams of sea water.’

Already the scene is unsettling, likely to grow ever more foreign as the man’s stay extends through the pages. It has been noted that the plot device starts to reveal itself only halfway into the book and although there is ample online revealing of the later events, I shall avoid giving the eventual storyline and ending. This causes a certain dilemma, not talking about the nature of ‘Morel’ himself, and his scheme. However, it can be said that an ‘eternal triangle’ develops, affecting the two males and a woman named Faustine. As there will be much talk of souls, one reflects on the possible ‘Faustian’ legend, if only as to the choice of name, there being no actual supernatural being in the story.

The man first has to contend with marshes, left behind by irregular and inexplicable heavy tides, often flooding the lowlands completely. He senses that the island has been populated in the past, but is now abandoned. The ‘Morel’ island has the peril of disease, with chances of starvation, or injury, or dealing with the presence of snakes. And yet, seemingly all at once, the more grassy and hilly area becomes crowded with people, who play music, dance and sing. For the lone male even this presents a danger, as he is wanted for some misdoing by another country and if he is reported he faces severe punishment. In this way his dual problems of understanding the mysteries of the island and his own survival lead the character and reader into ever more surreal situations. The man finds a large building, which he labels ‘the museum’, where he will have shelter from high winds and intense downpours, but more secrets lie within the inner surroundings and a closed basement. Hearing sounds and imagining ghosts increase the individual’s nervousness.

His circumstances are transformed by the appearance of the woman Faustine, who is always sitting not far off, watching each day’s sunsets. Bioy’s narrative allows such a pair of individuals to coexist spatially in two different temporal dimensions; sometimes there are even two suns to behold at the same time, or two moons. As the writer begins to add dialogue to the goings-on, the main character is drawn deeper into the plot, using his wits to decrypt what is happening, choosing how he can fight against darker pressures, while injecting himself into situations he will find pleasing. To his dismay the woman seems not to notice him.

‘Now the nightmare continues. I am a failure, and now I even tell my dreams. I want to wake up, but I am confronted with the sort of resistance that keeps us from freeing ourselves from our most atrocious dreams.’ He believes that Morel and the woman have a bond, while he himself struggles with feelings of isolation. He comes up with a series of hypotheses to explain his surroundings and the people who appear and vanish: ‘… this island may be the purgatory or the heaven of those dead people..’ adding, ‘The dead remain in the midst of the living. It is hard for them, after all, to change their habits…’ The notion occurs to the thinker that perhaps he is dead, unseen by those on the island who are living. ‘Thinking about these ideas left me in a state of euphoria… my relationship with the intruders was a relationship between beings on different planes.’ Such thoughts charge him, ‘So I was dead! The thought delighted me. (I felt proud, I felt as if I were a character in a novel!)’ It is these weighings which build up towards the discovery of what is behind the place and events, and the genius or madness of Morel.

However, the man remains fixated on the woman., fearing ‘losing’ her, as if she is more than a figment. He considers options, all to no avail, ‘… if I abduct her they will surely send out a search party, and sooner or later they will find us. Is there no place on this whole island where I can hide her?’ His musings are supplanted by the sight of the group of people going swimming, including of course his beloved. ‘Undressed, Faustine is infinitely beautiful. She had that rather foolish abandon people often have when they bathe in public, and she was the first one to dive into the water. I heard them laughing and splashing about gaily.’

As if the watcher is still keeping his journal, or diary, he relates happenings to the reader, so that his record or memories will not be lost. His mixed-up imaginings, or his failure to comprehend what is occurring, or both, is clear from his utterances. ‘I am going to relate exactly what I saw happen from yesterday afternoon to this morning, even though these events are incredible and defy reality. Now it seems that the real situation is not the one I described on the foregoing pages; the situation I am living is not what I think it is.’

More pages relate encounters, conversations, and deductions, often with combined feelings of déjà vu, recollections of past times, and thoughts of a future, even beyond death. The inexplicable doubling effect applies also to ordinary items. ‘I saw a ghostcopy of the book… that I had taken two weeks earlier,- it was on the same shelf of green marble, in exactly the same place on the shelf. I felt my pocket; I took out the book. I compared the two: they were not two copies of the same book, but the same copy twice.’ A similar but more dramatic aspect arises, in that if a perfect images of a person manifested itself, how would the observer know if the individual was real? In this regard, the importance of sensory awareness is stressed, ‘… sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch…’. If all these elements are present, is the experience real, or perhaps the product of some complete replication.

The man is still filling his diary with entries, trying to rationalise a feeling of ‘playing a dual role, that of actor and spectator.’ He recalls his initial writing in the journal, ‘I have the uncomfortable sensation that this paper is changing into a will.’ As for Faustine, he seems resigned, becoming accustomed to the idea of ‘spending my life in seraphic contemplation of her.’ Is there a rational explanation for his existence, and that of others he has seen, or as to the incomprehensible events he has witnessed? This is not to say that his world is a phantasm, something existing in perception only.

Bioy’s character appeals to ‘the person who nails this diary’, suggesting that there must be some reality surrounding the act of writing. Perhaps the whole adventure is real, which the diarist is explaining to some chance finder, while in Bioy’s world the story is simply an abstract confection, presented to the reader of his book.

‘The Invention of Morel’ was met with widespread acclaim and Bioy was eventually awarded Spanish literature’s greatest honour, the Cervantes Prize in 1991. For me, I wondered if the tale was originally born of Latin-American passion, its translation not synergising with the author’s own style, romantic language and nuancing. I hope to have concealed the main elements of the tale in this review; I did find the plotting, exposition and revelation impressive and some of the weaknesses I felt have been expounded upon online. The story just didn’t click with me and I was ashamedly relieved that it was only a novella.

As a postscript, I learned that the book and/or its author, was inspired by the legendary actress of the silent film era, Louise Brooks, also as a reaction to her screen career diminishing after the Twenties, as if Bioy dreamed of preserving her as she was at her height. In some small way his wish was met by having a photo of Brooks adorning the 2003 (above) printing of his 1940 creation.

Thanks Mr. K for sharing your thoughts on this book and contributing to the #1940Club! As you can see if you look at my review, I was a lot fonder of it than Mr. K is, but then it would be boring if we all liked the same thing, wouldn’t it??

1940 Club: All your reviews! #1940Club – Stuck in a Book

Apr 13, 2023 @ 10:14:36

Apr 13, 2023 @ 21:53:51

I would still offer this the benefit of the doubt and give it a go despite any reservations you might have; you certainly suggest enough to convey a sense of mystery and of depth. Oh, and it’s short, so that’s in its favour too!

Apr 14, 2023 @ 12:09:27

This is really not the type of book Mr K would normally read, so I wouldn’t necessarily take his reservations on board (valid as they may be – or not!) I personally loved the book and as you say, it’s short – so if you don’t take to it, you haven’t wasted much time!!

Apr 14, 2023 @ 01:03:52

Always lovely to have Mr. Kaggsy’s club review and this one is a nice balance of description and not spoiling anything vital. I only wish he had enjoyed it more! I loved the way the author explores time, perception, technology, and love. And the tension makes it difficult to put down.

Apr 14, 2023 @ 12:07:59

He says thank you! I think this is very much not his type of book so I’m quite impressed that he took it on. I loved it though, so just goes to show how tastes can differ, and I agree that it’s absolutely compelling!

Apr 14, 2023 @ 13:12:12

Lovely to see Mr K sharing his views with us again. A shame this didn’t completely work for him.

Apr 14, 2023 @ 15:19:18

No, not so much his kind of book but he did finish it, to do him justice! 😀

Apr 14, 2023 @ 19:39:47

Lovely to see a review from Mr K, especially as he presents such an interesting take on this intriguing novella. As I think you were saying earlier this week, it does seem to divide opinion. A good one for book groups perhaps given the range of different reactions…

Apr 14, 2023 @ 20:17:23

I certainly think it’s a Marmite book – there are so many differing opinions on it, and Mr. K and I view it very differently! And you’re right – it would be a great choice for a book group! 😀

Apr 21, 2023 @ 18:06:31

A clever review that doesn’t give anything away! I did feel it must be a much longer book from the description, but maybe it was a little wearing!

Apr 21, 2023 @ 20:30:24

It’s not so long but quite twisty and complex in places, so probably that’s what makes it seem a little longer!

May 02, 2023 @ 01:11:41

I also enjoyed it. A Marmite book fits this title, yes.

May 02, 2023 @ 15:38:32

Yes, I think it is very much so – I loved it!

May 25, 2023 @ 01:57:25

Too bad, This book was a big revelation for me.

May 25, 2023 @ 10:44:31

I loved it too, but it just wasn’t Mr. K’s cup of tea!