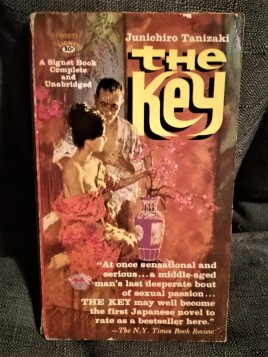

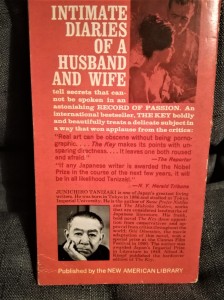

So far for the Japanese Literature Challenge I’ve explored an essay on aesthetics and a powerful memoir of nuclear attack; and I said at the end of my post on the latter than I imagined my next Japanese book this month would be a little lighter. Well, it certainly was a slim volume of fiction; however, the subject matter was complex and left me thinking a lot about the relationships between men and women. In my first Japanese post on Jun’ichirō Tanizaki I mentioned that I would have to look on the TBR and see if I had anything else by him; I do, and that’s the book I want to talk about today – “The Key”, published in a translation by Howard Hibbett in 1960. And as you can see from the rather lurid covers of my US Signet Books edition, sexual passion is at the heart of the book…

“The Key” is one of Tanizaki’s later books, and it takes the form of diary entries; these are drawn from the journals kept separately by a husband and wife, a 55 year old Professor, and his 44 year old wife Ikuko. They live with their grown up daughter Toshiko, and the Professor has singled out one of his young teachers, Kimura as a possible husband for Toshiko. However, all is not well with the marriage. The Professor claims to adore his wife but feels that he cannot satisfy her sexually, and is concerned that she is too refined to let him indulge his passion for her, even to see her fully naked.

Ikuko, however, is conflicted; one minute she claims to love her husband, the next to hate him and find him repulsive. It may be the age difference; it may be that she has retained her looks despite having a child, whereas he is an unhealthy, unattractive specimen; or it may be that she is attracted by the virility and youth of Kimura. The reader watches what happens, and the possible development of a menage-a-trois or even a-quatre – all the while realising that what they are reading is filtered through the sensibilities of both parties in the marriage, presenting in their diaries what they want their partner to be secretly reading (all the while denying that they are reading the other’s journal).

And now I hit the dilemma of how much more to discuss the plot; because I came to this book with no knowledge of the story or preconceptions, and I think that’s the best way to read it! Tanizaki very cleverly lets his tale develop from the two separate viewpoints of the married couple and the reader is left to read between the lines and work out what’s *really* going on; much is confirmed at the climax of the book (ahem…) but plenty is left unresolved… There are plot elements I can’t mention specifically, but which are to do with the Professor’s treatment of his wife; however, her diaries reveal that she is more in control of what is happening, and actually stimulated by it, than her husband might think!

As I mentioned above, my mid-20th century addition has a cover which is covered with sensationalist blurb; so you may be wondering whether the book is as torrid as is made out. Frankly, I would say it’s very mild compared with modern media of all kinds but probably *was* quite shocking at the time. There is nothing graphic or particularly gratuitous but the frank discussion of sexual needs (particularly that of a woman) was possibly groundbreaking. The behaviour of the couple towards each other, although again nothing really graphic occurs, is fairly shocking and at the time would have disturbed Western sensibilities – I imagine the traditional American could have been a bit outraged!

Why should he have dropped the key in a place like that? Has he changed his mind and decided he wants me to read it? Perhaps he realises I’d refuse if he asked me to, so he’s telling me: ‘You can read it in private – here’s the key.’ Does that mean he thinks I haven’t found it? No, isn’t he saying rather: From now on I acknowledge that you’re reading it, but I’ll keep on pretending you’re not?’

Well, never mind. Whatever he thinks, I shall never read it.

Putting all that aside, how does the book read to this modern reader? Very well, actually; I can imagine that readers much younger than me would be rather cross about some elements, but I think that’s perhaps a fairly shallow response. Without wanting to give anything much away, both parties to the marriage are guilty – of lack of communication, of not respecting each other’s wishes or needs or feelings, and of manipulating the other. So there are not necessarily any victims – or if there is, it’s not the victim you might expect! As for the key of the title, well that refers to the one the Professor uses to lock his diary in his desk drawer then leaves lying around for his wife to find and open the drawer… Twists abound from the very first page of this novella! 😉

I’m sorry if this is all a bit vague in places but I’m trying desperately not to give anything away. Suffice to say that Tanizaki brilliantly portrays a pair of unreliable narrators, gradually teasing out the story to its dramatic fulfilment and “The Key” is a very clever, very readable and actually very thought-provoking book. If nothing else, it certainly convinces the reader that a good relationship is based on communication

Jan 16, 2023 @ 07:19:42

I can’t tell you how much I’m enjoying everyone discovering the Japanese classics – Vishy with Natsume Soseki, you with Tanizaki… Perhaps it’s time I reread all of them and see if I still feel any differently about them than I did in my early 20s.

Jan 16, 2023 @ 10:53:15

I’m a huge fan of these Japanese classics and loving exploring them – makes me wonder why I’ve had them unread on the TBR for so long! Would be interesting to hear what you think of them now on a re-read!

Jan 16, 2023 @ 09:29:37

Excellent review. It is a very good book by an excellent writer. Very economical with much hinted at and a lot left to the reader to unpick. I *adore* that cover, much better than my old copy (which, I’m sad to say, I don’t seem to possess anymore).

If you enjoyed The Key then I think you’ll also enjoy Diary of a Mad Old Man which is similarly….fruity in tone.

Jan 16, 2023 @ 10:52:09

Thank you! I thought this was such a clever book and as you say, a lot to unpick which I enjoy. As for the cover – yes, it’s very striking isn’t it? I really do want to read more of him now…

Jan 16, 2023 @ 11:06:23

A very enticing review! The book sounds intriguing. I remember reading and very much enjoying The Makioka Sisters years ago but haven’t read anything else by Tanizaki. Adding this one to my list.

Jan 16, 2023 @ 11:31:21

It’s fascinating and so very clever! I really want to get to more of his works, and luckily have several on the TBR! 😀

Jan 16, 2023 @ 12:32:36

What an interesting way to approach what marriage is and how the different parties feel about it. And the two different diaries/viewpoints remind me of another Japanese novel, Higashino’s Malice, in which the reader is invited to make sense of what really happened, based on two different perceptions. I always think that can be a really effective way to draw the reader in.

Jan 16, 2023 @ 15:38:49

It’s a very clever way to tell the story, and it does keep you on your toes as you read through, realising how the narrative is what each party wants the other one to believe. Very cleverly done and very engrossing!

Jan 17, 2023 @ 01:00:00

What this reminds me of more than anything is the way the Tolstoys used their diaries to do battle with each other. That cover is so typical of the pulpy designs mass market paperback houses used en masse for everything. And happily collected these days!

Jan 17, 2023 @ 14:31:15

That’s a good analogy – I really want to read Sophia’s side of the story! And although the cover is a little garish, I do like that style of design!!

Jan 17, 2023 @ 11:06:30

That cover is dire, but the novella sounds interesting, I like that it puts across twin perspectives and leaves it to the reader to figure things out. So much of what we read and how we see it reflects something we bring to the page and I often enjoy how vastly different the reader opinions are regarding books like this that expose the inner thoughts of a character honestly.

I’ve just finished Yuko Tsushima’s Child of Fortune, which is only of one woman’s perspective, but the honesty of her thoughts and dreams makes many readers unsympathetic to her as a character. I found her fascinating, as she was a ‘break away from convention’ character, unsupported emotionally by those around her, often prone to harsh self judgement.

Wonderful and enticing review Kaggsy!

Jan 17, 2023 @ 14:28:21

Thank you! 😀

The cover is dire, yes, but very much of its time – and I suppose it has a certain period charm!!

As for the book, it’s so clever – as you say, this really does leave the author to do a lot of work and I enjoyed that a lot. The gradual reveal of what’s really going on is brilliant!.

Tsushima, from what I’ve read, is a wonderful author – I’ve only encountered her short stories and get what you say about her character, but that doesn’t bother me – a fascinating read!

Jan 17, 2023 @ 20:51:26

I love Tanizaki – though the last one I read, The Maids, was not his best. You make me want to re-read this – and I agree, the cover has a ‘certain period charm’!

Jan 18, 2023 @ 14:10:04

It has! Although the blurb is very OTT, the cover itself is quite attractive! The book itself was very enjoyable too, and I’m determined to read more of his work!

Jan 19, 2023 @ 18:39:18

This sounds really clever, and you’ve made it so enticing while avoiding spoilers.

I probably shouldn’t admit this but I love a kitschy 1960s cover 😀

Jan 19, 2023 @ 20:06:32

It’s a hard book to write about without revealing too much, so I’m glad I enjoyed spoilers.

And yes – tbh, I do rather like the cover myself… ;D

Jan 21, 2023 @ 17:43:56

Your Japanese reading has been interesting, this sounds very intriguing. The diary entries are a clever way of exploring the relationship between the two characters.

Jan 22, 2023 @ 12:46:21

I’ve read some lovely Japanese books this month, and as they’re pretty much all off the TBR that has to be good! This one was particularly interesting and very cleverly done!

Jan 24, 2023 @ 07:10:34

What an interesting book but what a terribly lurid cover!! You have had a good Japanese Literature month and off the TBR as well. I do read Japanese books from time to time but I never seem to have anything in when it’s time for this one (1940 Week, now, that’s a different story: see my upcoming blog post today!).

Jan 24, 2023 @ 11:17:42

LOL, the cover is very much of its time, but the book was marvellous! I’ve loved my Japanese reading this month and am so happy to be reading from the TBR! As for 1940 – off to check out your post!!